Sections in this article

Introduction

Globalisation, the Internet, and the widespread accessibility of information and communication technologies are major reasons why learning is becoming the most important competence to master in order to succeed in life, society, and work. Only a couple of decades ago it was suggested that reading, writing, and numeracy skills were enough to cope with the demands of the modern world. Today, however, people are faced with not only the need to constantly acquire new competencies, but these competencies must also be constantly updated. Learning has moved from being a foundation for life towards being a lifelong process and requirement. A side effect of these changes is that learning is moving outside of schools and other educational establishments; freely available learning content, such as the Khan Academy (a library of over 3,200 educational videos), videolectures.net (a portal for exchanging ideas and sharing knowledge), and Coursera (offering whole university courses for free), will soon enrol more students than traditional schools. These developments are having a dramatic impact on schools and teachers, whose focus must switch from only providing knowledge to enabling people to learn throughout their lives.

Throughout history there have been numerous theories and myths about how learning takes place. Traditionally, learning was the domain of philosophy, and only towards the end of the 19th century did scientific research on memory begin. Theories developed by psychologists dominated the learning discourse in the 1970-80s, while more recently advances in neuroscience continue to produce relevant insights into how our brains and memories work. This chapter outlines a number of these theories and draws some conclusions that remain valid over time.

Memorising information

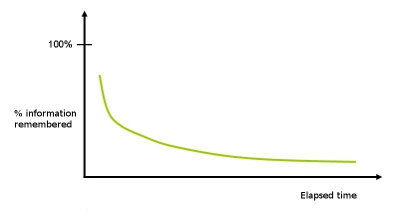

In the early 1880s the German scientist Hermann Ebbinghaus began to scientifically study memory. He did this by inventing words without meaning and applying different strategies to memorise them. His work lead to insights into the importance of repetition and how people remember information over time. His most famous legacy is the “forgetting curve”, which shows the exponential loss of information that one has learned:

Ebbinghaus’ work was later criticised because he worked with information that lacked any meaning, which is not the way learning usually takes place. Nonetheless, some relevant lessons can be learned from his research, especially for the effective memorisation of information such as vocabulary. While repetition is important, there is not much benefit to repeating things one already knows. A more efficient approach is to focus on things that prove difficult to remember and to increase the time span between instances of repetition. This strategy is reflected in the popular vocabulary card box, which also forms the basis for many software-based vocabulary training programmes. In this system cards with the information one wants to memorise are grouped in five boxes of increasing size. Information that is remembered by the learner moves into the next box, but forgotten information goes back into the first box. This approach ensures that one focuses on information that is not yet memorised and that the time span between instances of repetition for remembered information is constantly increasing.

Conclusions

Although memorising huge amounts of information has become less important in the age of the Internet, it is still relevant in some professions and plays an important role in learning languages. Repetition also remains the most important learning strategy for memorising any kind of information. A major shortcoming of many adult education courses is that participants will not repeat learned information, thus it never reaches the long-term memory and is quickly forgotten. While schoolchildren and university students must regularly repeat learned information, for example, when writing assignments or preparing for exams, this is not the case in shorter learning settings.

Learning styles

Psychologists have developed several models that try to categorise the different ways in which people learn. One of the more famous models is the VARK model (or VAK model), developed by Neil D. Fleming, which differentiates four different types of learning preferences:

- Visual: These learners prefer graphic illustrations, for example, maps, diagrams, and charts.

- Aural: Learners with an auditory preference prefer verbal information, for example, listening to a lecture or group discussions.

- Read: These learners prefer text-based information, such as manuals, handouts, and Powerpoint presentations.

- Kinesthetic: For these learners physical activity is important, which helps them to apply information to reality, for example, through simulations.

Conclusions

Categorisations such as this one highlight that people learn differently and that there is no “one fits all” approach. But the scientific validity of these models is hard to prove and recent findings in the field of neuroscience show that learning always involves several sensory channels. In any case, there is no doubt that people have differing learning preferences and habits that must be taken into consideration during the teaching process, and all learners will benefit from the use of a variety of sensory channels. The teacher should therefore always try to integrate methods that address all types of information: visual, auditory, verbal, and practice-oriented information.

This coincides with the hugely popular theory that people remember 10% by reading information, 20% by seeing it, 30% by hearing, 50% by seeing and hearing, 70% by collaboration, and 80% by doing. There is substantial doubt as to whether these figures have any scientific foundation, but its implications are nonetheless valid, namely, that a multi-sensory approach to teaching will be most effective and that the best learning results will be achieved if the learners are actively engaged in the learning process.

Findings from neuroscience

Brain research shows that there is no such a thing as one memory; language, movement, visual processing, and adding value to information takes place in different areas of the brain. Scientists have managed to gain a fairly good understanding of how these processes take place, but their discoveries are only slowly finding their way into applied teaching.

The brain is always changing. It remains plastic throughout life and as a result a healthy person can learn and change regardless of his/her age. Yet it must also be said that certain abilities do decrease with age; for example, over time it becomes more difficult to recall information and it takes an older person longer to adapt to new situations. The good news is that people are very able to compensate for these physical shortcomings by putting their life experience to use and developing their own coping strategies.

A more significant obstacle is that many adults have forgotten how to learn. It does not help that the education system has often not been effective in developing “learning to learn” skills in the first place. Especially in situations where people have failed the education system (or the education system has failed them) it is advisable to introduce learners with tools that will help them in their learning efforts, such as active reading strategies, mind mapping, and memorising techniques (often called “mnemonics” in reference to the Greek goddess Mnemosyne, who personified memory).

Interestingly, experiments show that motivation has no direct impact on learning effectiveness. The role of motivation is indirect; motivation determines how much time a person will spend and how great an effort he/she will make to learn something.

Two sides of the brain

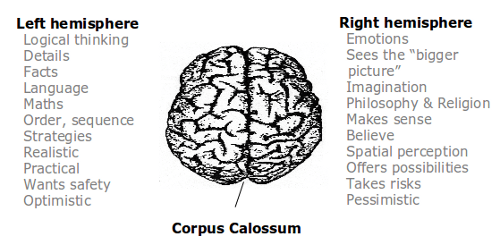

Roger Sperry’s findings regarding the division of the brain into a right and left hemisphere with specific functions allocated to each of them is another theory with relevance to learning.

The human brain is divided into two hemispheres. Each of them has its primary functions: For most people the left side of the brain focuses on logical thinking, details, facts, language, mathematics, order, sequence, strategies, reality, and safety. The right side tends to focus on emotions, seeing “the big picture”, imagination, symbols and images, meaning, belief, spatial awareness, and risk taking.

Direct implications of the brain divide for learning are limited because both hemispheres are nevertheless closely linked through a vast number of fibre connections. Therefore in practice the two brain hemispheres act more or less as one entity. Still, this model is useful for describing a number of challenges that traditional education faces and it underlines some principles for effective teaching.

The brain divide is a good metaphor to describe changes that people are facing today. The functions allocated to the left hemisphere represent competencies that were important in the 20th century when the role model outcome of the Western education system was an individual with strong logical thinking and analytical skills, one who drew attention to details, was able to structure information, had strong verbal skills, and did not take on unnecessary risks. These were competencies that the 20th century labour market was looking for and which still dominate many areas of society. However, these competencies are no longer enough to be successful in the 21st century. Several changes have occurred:

- Most people’s biographies are not as straight-forward as they used to be. Earlier, a person typically gained an education, then found a job, climbed the career ladder, founded a family, and finally retired. Nowadays the life trajectories of many people follow a more non-standard path.

- The amount of available information has become too vast and complex to be put into hierarchical order or to be analysed with traditional analysing methods.

- More and more work processes are replaced by computers or cheaper labour in other countries, which means that even low-skilled jobs become more demanding and require additional competencies such as team work, basic foreign language skills, and digital literacy.

These changes result in an increase in the importance of functions typical of the right hemisphere of the brain. People nowadays must make use of available opportunities and apply problem solving skills in order to learn to not get lost in the vast amount of information available.

Conclusions for teaching

- Adult learners will be motivated to make an effort if they see why the topic / information is important to them.

- Consider that people learn differently. Group work is an important tool for dealing with different knowledge levels and interests.

- Address various sensory channels when presenting information.

- Show “the bigger picture”; for example, in the beginning of the course present the whole content and explain why it is important.

- When presenting new information, show how it connects to what people already know or do.

- Help learners deal with new information by creating a stress-free environment and by ensuring that the environment is well structured.

- A variety of competences can be developed in any teaching subject, such as problem solving, team work, or learning to learn skills.